what must a plaintiff prove as a holder in due course to a retail installment agreement

19.4 Cases

Negotiability: Requires Unconditional Promise to Pay

Holly Loma Acres, Ltd. five. Charter Bank of Gainesville 314 Then.2nd 209 (Fla. App. 1975)

Scheb, J.

Appellant/defendant [Holly Hill] appeals from a summary judgment in favor of appellee/plaintiff Depository financial institution in a suit wherein the plaintiff Depository financial institution sought to foreclose a notation and mortgage given past defendant.

The plaintiff Bank was the assignee from Rogers and Blythe of a promissory annotation and purchase money mortgage executed and delivered by the defendant. The note, executed April 28, 1972, contains the following stipulation:

This notation with interest is secured by a mortgage on real estate, of even date herewith, fabricated by the maker hereof in favor of the said payee, and shall be construed and enforced according to the laws of the State of Florida. The terms of said mortgage are by this reference made a part hereof. (emphasis added)

Rogers and Blythe assigned the promissory notation and mortgage in question to the plaintiff Banking concern to secure their own notation. Plaintiff Bank sued defendant [Holly Hill] and joined Rogers and Blythe as defendants alleging a default on their note equally well as a default on defendant's [Holly Hill's] notation.

Defendant answered incorporating an affirmative defense that fraud on the function of Rogers and Blythe induced the sale which gave rise to the buy money mortgage. Rogers and Blythe denied the fraud. In opposition to plaintiff Bank'south motion for summary judgment, the defendant submitted an affirmation in support of its allegation of fraud on the function of agents of Rogers and Blythe. The trial courtroom held the plaintiff Bank was a holder in due course of the note executed by defendant and entered a summary final judgment against the defendant.

The annotation having incorporated the terms of the purchase money mortgage was not negotiable. The plaintiff Bank was non a holder in due grade, therefore, the defendant was entitled to heighten confronting the plaintiff any defenses which could be raised between the appellant and Rogers and Blythe. Since defendant asserted an affirmative defence force of fraud, it was incumbent on the plaintiff to establish the non-existence of whatever genuine issue of any material fact or the legal insufficiency of defendant'southward affirmative defense. Having failed to do then, plaintiff was not entitled to a judgment as a matter of constabulary; hence, we opposite.

The note, incorporating past reference the terms of the mortgage, did not contain the unconditional promise to pay required past [the UCC]. Rather, the annotation falls within the scope of [UCC 3-106(a)(ii)]: "A promise or club is unconditional unless information technology states that…information technology is subject field to or governed by any other writing."

Plaintiff Banking concern relies upon Scott five. Taylor [Florida] 1912 [Citation], equally dominance for the proposition that its note is negotiable. Scott, all the same, involved a note which stated: "this annotation secured by mortgage." Mere reference to a note beingness secured by mortgage is a common commercial practice and such reference in itself does not impede the negotiability of the note. There is, yet, a pregnant deviation in a note stating that information technology is "secured by a mortgage" from one which provides, "the terms of said mortgage are by this reference made a part hereof." In the former instance the note only refers to a separate agreement which does not impede its negotiability, while in the latter instance the note is rendered non-negotiable.

As a full general dominion the assignee of a mortgage securing a non-negotiable note, fifty-fifty though a bona fide purchaser for value, takes bailiwick to all defenses bachelor as against the mortgagee. [Citation] Defendant raised the issue of fraud as between himself and other parties to the notation, therefore, it was incumbent on the plaintiff Banking company, as movant for a summary judgment, to testify the non-existence of any genuinely triable effect. [Citation]

Accordingly, the entry of a summary final judgment is reversed and the crusade remanded for further proceedings.

Case Questions

- What was wrong with the promissory annotation that fabricated it nonnegotiable?

- How did the note's nonnegotiability—as determined by the court of appeals—benefit the defendant, Holly Hill?

- The court determined that the bank was not a holder in due course; on remand, what happens now?

Negotiability: Requires Fixed Amount of Coin

Centerre Depository financial institution of Branson v. Campbell 744 S.W.2d 490 (Mo. App. 1988)

Crow, J.

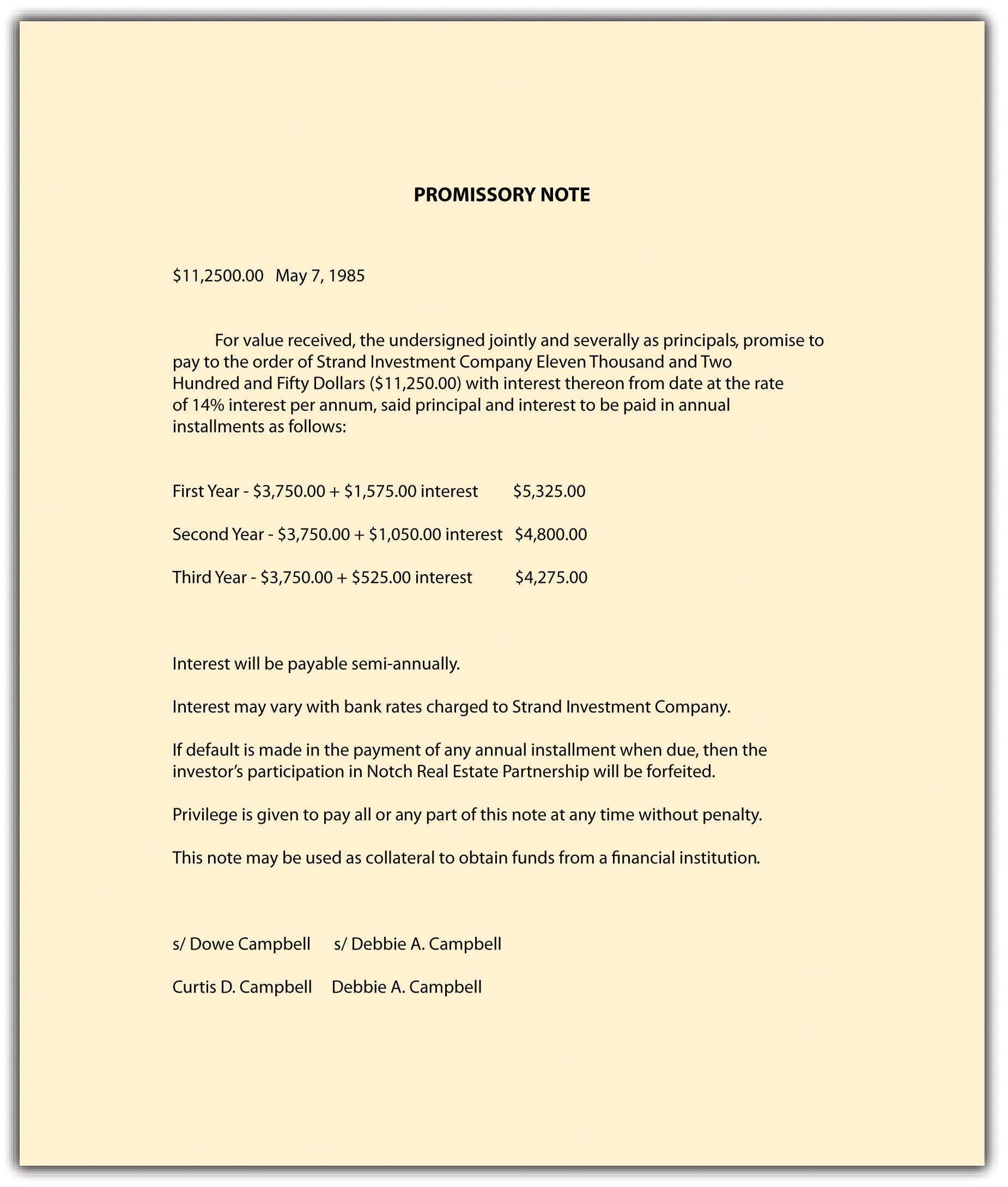

On or well-nigh May vii, 1985, appellants ("the Campbells") signed the following document:

Effigy 19.5

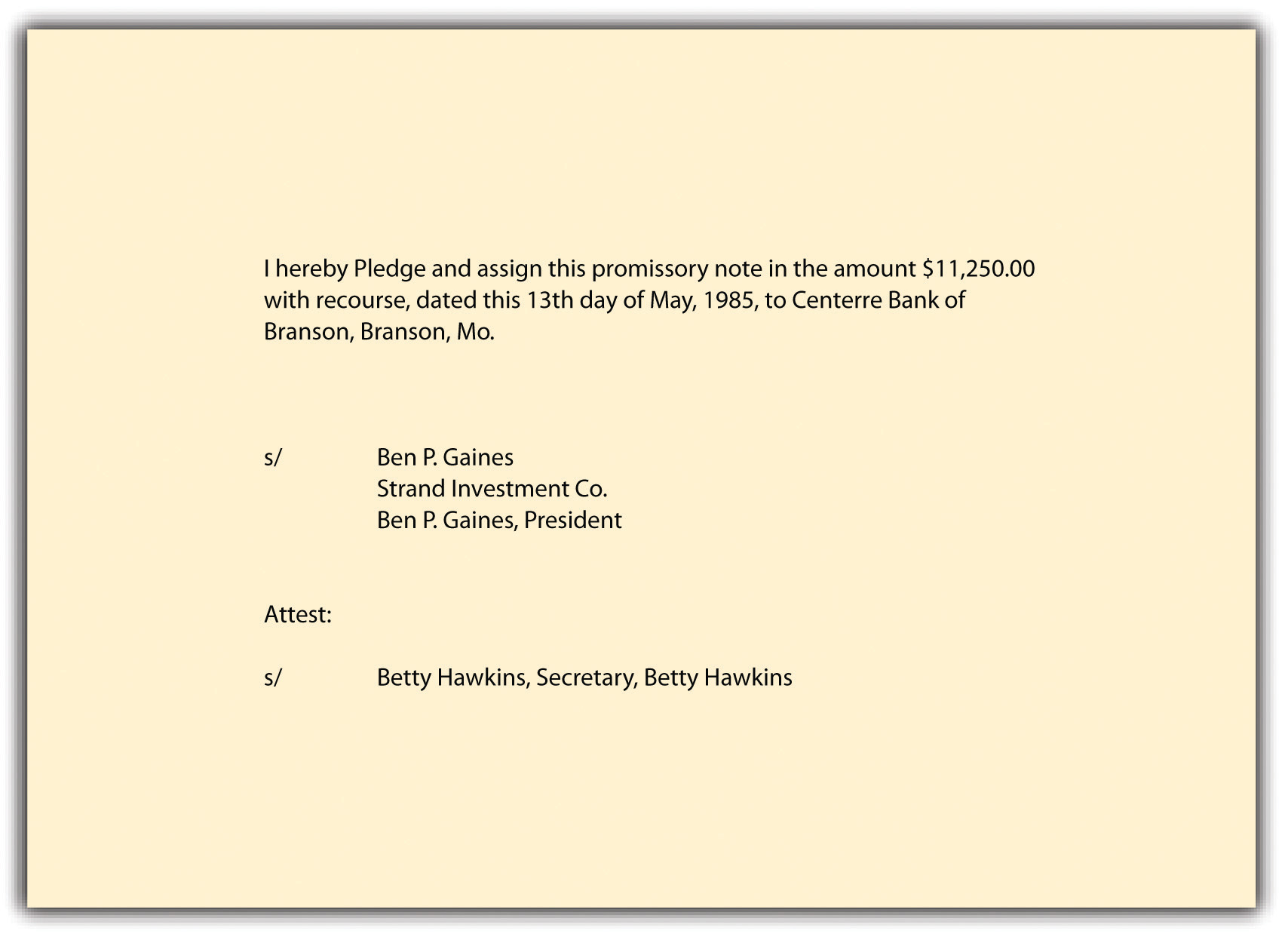

On May 13, 1985, the president and secretarial assistant of Strand Investment Visitor ("Strand") signed the following provision [see Figure 22.6] on the reverse side of the above [Figure 19.5] document:

Effigy nineteen.6

On June 30, 1986, Centerre Bank of Branson ("Centerre") sued the Campbells. Pertinent to the bug on this entreatment, Centerre's petition averred:

"1. …on [May 7,] 1985, the [Campbells] made and delivered to Strand…their promissory annotation…and thereby promised to pay to Strand…or its order…($11,250.00) with interest thereon from engagement at the rate of fourteen pct (14%) per annum; that a copy of said promissory note is fastened hereto…and incorporated herein by reference.

2. That thereafter and before maturity, said notation was assigned and delivered by Strand…to [Centerre] for valuable consideration and [Centerre] is the owner and holder of said promissory note."

Centerre's petition went on to allege that default had been fabricated in payment of the annotation and that at that place was an unpaid principal balance of $9,000, plus accrued involvement, due thereon. Centerre'southward petition prayed for judgment against the Campbells for the unpaid chief and interest.

[The Campbells] aver that the note was given for the purchase of an interest in a limited partnership to be created by Strand, that no limited partnership was thereafter created past Strand, and that by reason thereof there was "a complete and full failure of consideration for the said promissory note." Consequently, pled the answers, Centerre "should be estopped from asserting a claim against [the Campbells] on said promissory note because of such total failure of consideration for same."

The crusade was tried to the courtroom, all parties having waived trial by jury. At trial, the attorney for the Campbells asked Curtis D. Campbell what the consideration was for the note. Centerre's chaser interrupted: "We object to any testimony every bit to the consideration for the note because information technology'south our position that is not a defence force in this lawsuit since the bank is the holder in due course."…

The trial court entered judgment in favor of Centerre and confronting the Campbells for $ix,000, plus accrued interest and costs. The trial courtroom filed no findings of fact or conclusions of law, none having been requested. The trial court did, however, include in its judgment a finding that Centerre "is a holder in due course of the promissory note sued upon."

The Campbells appeal, conference 4 points. Their first iii, taken together, nowadays a unmarried hypothesis of error consisting of these components: (a) the Campbells showed "by clear and convincing testify a valid and meritorious defense in that there existed a full lack and failure of consideration for the promissory note in question," (b) Centerre acquired the note subject to such defense in that Centerre was not a holder in due class, equally one can be a holder in due course of a annotation only if the annotation is a negotiable musical instrument, and (c) the note was non a negotiable instrument inasmuch as "it failed to state a sum sure due the payee."…

We have already noted that if Centerre is not a holder in due grade, the Campbells can affirm the defense of failure of consideration against Centerre to the aforementioned degree they could have asserted information technology against Strand. We have as well spelled out that Centerre cannot be a holder in due course if the notation is non a negotiable musical instrument. The pivotal issue, therefore, is whether the provision that interest may vary with bank rates charged to Strand prevents the note from being a negotiable instrument.…

Neither side has cited a Missouri case applying [UCC 3-104(a)] to a notation containing a provision like to: "Interest may vary with bank rates charged to Strand." Our independent enquiry has also proven fruitless. At that place are, still, instructive decisions from other jurisdictions.

In Taylor v. Roeder, [Citation, Virginia] (1987), a note provided for interest at "[t]hree percent (3.00%) over Chase Manhattan prime number to be adjusted monthly." A second notation provided for interest at "three% over Chase Manhattan prime number adapted monthly." Applying sections of the Uniform Commercial Lawmaking adopted by Virginia identical to [the Missouri UCC], the court held the notes were non negotiable instruments in that the amounts required to satisfy them could not be ascertained without reference to an extrinsic source, the varying prime number rate of interest charged by Chase Manhattan Bank.

In Branch Cyberbanking and Trust Co. v. Creasy, [Citation, North Carolina] (1980), a guaranty agreement provided that the aggregate amount of principal of all indebtedness and liabilities at any one fourth dimension for which the guarantor would exist liable shall not exceed $35,000. The court, emphasizing that to exist a negotiable instrument a writing must contain, among other things, an unconditional hope to pay a sum certain in money, held the agreement was not a negotiable instrument. The opinion recited that for the requirement of a sum certain to exist met, information technology is necessary that at the fourth dimension of payment the holder be able to decide the amount which is then payable from the musical instrument itself, with any necessary computation, without reference to whatsoever outside source. Information technology is essential, said the court, for a negotiable musical instrument "to bear a definite sum so that subsequent holders may accept and transfer the instrument without having to plumb the intricacies of the instrument's groundwork.…

In A. Alport & Son, Inc. five. Hotel Evans, Inc., [Citation] (1970), a note contained the notation "with interest at bank rates." Applying a department of the Uniform Commercial Code adopted by New York identical to [three-104(a)] the court held the note was not a negotiable instrument in that the amount of interest had to be established by facts outside the instrument.

In the instant case, the Campbells insist that it is impossible to determine from the confront of the annotation the amount due and payable on whatsoever payment date, as the note provides that interest may vary with bank rates charged to Strand. Consequently, say the Campbells, the annotation is not a negotiable instrument, as it does non contain a promise to pay a "sum certain" [UCC 3-104(a)].

Centerre responds that the provision that interest may vary with bank rates charged to Strand is not "directory," merely instead is just "discretionary." The statement begs the question. Fifty-fifty if ane assumes that Strand would elect not to vary the interest charged the Campbells if interest rates charged Strand past banks inverse, a holder of the note would have to investigate such facts earlier determining the amount due on the note at any fourth dimension of payment. We agree that nether iii-104 and iii-106, supra, and the authorities discussed before, the provision that interest may vary with bank rates charged to Strand bars the note from being a negotiable musical instrument, thus no assignee thereof tin can be a holder in due course. The trial court therefore erred every bit a matter of law in ruling that Centerre was a holder in due class.…

An warning reader will take noticed two other extraordinary features about the note, not mentioned in this opinion. Outset, the note provides in one identify that principal and interest are to be paid in annual installments; in another place it provides that involvement will be payable semiannually. Second, there is no dispatch clause providing that if default be made in the payment of any installment when due, then all remaining installments shall become due and payable immediately. It would have thus been arguable that, at time of trial, only the first year's installment of principal and interest was due. No issue is raised, however, regarding any of these matters, and we decline to consider them sua sponte [on our own].

The judgment is reversed and the crusade is remanded for a new trial.

Case Questions

- What was lacking near this annotation that fabricated it nonnegotiable?

- What was the consequence to Centerre of the court's determination that the notation was nonnegotiable?

- What did the Campbells give the annotation for in the first place, and why do they deny liability on information technology?

Undated or Incomplete Instruments

Newman v. Manufacturers Nat. Bank of Detroit 152 N.Due west.2nd 564 (Mich. App. 1967)

Holbrook, J.

Every bit testify of [a debt owed to a business associate, Belle Epstein], plaintiff [Marvin Newman in 1955] drew 2 checks on the National Banking company of Detroit, i for $1,000 [about $8,000 in 2010 dollars] and the other for $200 [about $1,600 in 2010 dollars]. The checks were left undated. Plaintiff testified that he paid all merely $300 of this debt during the post-obit side by side four years. Thereafter, Belle Epstein told plaintiff that she had destroyed the 2 checks.…

Plaintiff never notified defendant Bank to end payment on the checks nor that he had issued the checks without filling in the dates. The date line of National Bank of Detroit cheque forms independent the kickoff 3 numbers of the year but left the final numeral, month and day entries, bare, viz., "Detroit 1, Mich. _ _ 195_ _." The checks were cashed in Phoenix, Arizona, April 17, 1964, and the engagement line of each check was completed…They were presented to and paid past Manufacturers National Banking concern of Detroit, Apr 22, 1964, nether the endorsement of Belle Epstein. The plaintiff protested such payment when he was informed of information technology about a month subsequently. Defendant Banking concern denied liability and plaintiff brought suit.…

The ii checks were dated April 16, 1964. It is truthful that the dates were completed in pen and ink subsequent to the appointment of issue. However, this was not known by defendant. Defendant had a correct to rely on the dates appearing on the checks as being correct. [UCC 3-113] provides in function as follows:

(a) An instrument may be antedated or postdated.

Also, [UCC three-114] provides in part as follows:

[T]ypewritten terms prevail over printed terms, handwritten terms prevail over both…

Without notice to the contrary, defendant was inside its rights to assume that the dates were proper and filled in by plaintiff or someone authorized past him.…

Plaintiff admitted at trial that defendant acted in proficient faith in honoring the two checks of plaintiff's in question, and therefore accused's adept faith is non in issue.

In lodge to determine if defendant bank'south action in honoring plaintiff'due south 2 checks nether the facts present herein constituted an practise of proper process, we plow to article iv of the UCC.…[UCC 4-401(d)] provides as follows:

A bank that in good faith makes payment to a holder may charge the indicated account of its customer according to: (1) the original tenor of his altered item; or (2) the tenor of his completed detail, fifty-fifty though the depository financial institution knows the item has been completed unless the depository financial institution has notice that the completion was improper.

…[W]e conclude it was shown that two checks were issued by plaintiff in 1955, filled out simply for the dates which were subsequently completed by the payee or someone else to read April 16, 1964, and presented to defendant bank for payment, April 22, 1964. Applying the rules set forth in the UCC as quoted herein, the activeness of the defendant bank in honoring plaintiff's checks was in adept organized religion and in accord with the standard of care required under the UCC.

Since we have determined that there was no liability under the UCC, plaintiff cannot succeed on this appeal.

Affirmed.

Case Questions

- Why does handwriting command over printing or typing on negotiable instruments?

- How could the plaintiff have protected himself from liability in this example?

Source: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_legal-aspects-of-corporate-management-and-finance/s22-04-cases.html

Postar um comentário for "what must a plaintiff prove as a holder in due course to a retail installment agreement"